The Superbug Wars

Antibiotic resistance represents one of the greatest threats to modern medicine. Bacteria are evolving strategies that make our drugs ineffective, leaving clinicians with fewer treatment options and leading to increased mortality worldwide.

The CDC estimates that every year, antibiotic-resistant bacteria and fungi cause 2.8 million infections in the United States alone, resulting in more than 35,000 deaths. Globally, the situation is even more alarming. The World Health Organization (WHO) has declared antimicrobial resistance one of the biggest public health threats of the 21st century.

Antimicrobial resistance occurs when microbes—including bacteria—no longer respond to the drugs designed to eliminate them. Resistance is not a failure of the patient’s body; it’s a success of microbial evolution. Pathogens accumulate mutations or borrow resistance genes from neighbors, ensuring survival under the selective pressure of antibiotics. The more often bacteria are exposed to antibiotics—whether in clinical settings, agriculture, or even incomplete prescriptions—the more opportunities they have to adapt making small changes in their DNA. Over time, these small genetic changes add up, leading to “superbugs”: pathogens resistant to multiple drugs.

Understanding Antibiotic Resistance

Antibiotic-resistant bacteria, often called "superbugs," are microorganisms that have developed the ability to survive treatments that once killed them. These microorganisms have evolved a range of strategies to protect themselves.

One of these strategies is through genetic mutations. Bacteria accumulate small, random changes in their DNA that alter the proteins inside their cells. Most of these changes are neutral or even harmful for them and don’t get passed on to future generations, but occasionally one of these changes affects the very protein an antibiotic is designed to attack. When that happens, the drug can no longer bind effectively, and the bacterium gains a survival edge. These advantageous mutations are passed on to future generations and, under the constant pressure of antibiotic use, are strongly favored by natural selection—resistance, in other words, is evolution in action.

But not only that, bacteria also share resistance genes with their neighbors through horizontal gene transfer—a microbial version of file sharing that allows traits to spread quickly between species. Certain bacteria can even break down antibiotics with enzymes like beta-lactamases or use efflux pumps to push the drugs out before they do any harm. The repeated use of antibiotics then creates strong selection pressure, ensuring that resistant strains are the ones that survive and multiply. Because of this adaptability, resistance develops far faster than new antibiotics can be discovered. Once established, these traits spread with remarkable speed, finding new hosts in hospitals, farms, and communities—and with the help of global travel, crossing borders with ease.

Here are some of those “superbugs” that keep clinicians and public health officials up at night:

Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB: Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii) – A master survivor, persisting on hospital surfaces and equipment. Most strains resist carbapenems, and some resist nearly all antibiotics.

Campylobacter – Foodborne infections from undercooked poultry or unpasteurized milk are increasingly resistant to fluoroquinolones and macrolides.

Candida auris – A fungal superbug resistant to all three major antifungal drug classes. Outbreaks in hospitals are notoriously difficult to control.

Enterobacteriaceae (ESBL- and carbapenem-resistant strains) – These bacteria produce enzymes that dismantle critical antibiotics, including last-resort carbapenems. Escherichia coli, for example, a bacteria that can cause urinary tract infections, has developed resistance to fluoroquinolones as well. Or Klebsiella pneumoniae, a common intestinal bacterium that is now a major cause of hospital-acquired infections such as pneumonia, bloodstream infections and infections in newborns and intensive-care unit patients due to the acquired resistance to a last-resort treatment.

Enterococcus (VRE: Vancomycin-resistant Enterococci) – Up to 30% of healthcare-associated infections involve vancomycin-resistant strains, with limited treatment options.

Shigella – Easily spread through contaminated food or water. Resistance to azithromycin has surged since 2013.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa – Especially dangerous for immunocompromised patients, with strains resistant to nearly all antibiotics.

Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) – Resistant to many first-line antibiotics, causes life-threatening bloodstream and skin infections.

Streptococcus pneumoniae – Causes pneumonia, meningitis, and bloodstream infections. Vaccines help, but resistance to penicillin and macrolides remains a concern.

Apart from bacteria, viruses also adapt and develop resistance to anti-viral drugs. HIV drug resistance is caused by changes in the genetic structure of HIV that affect the ability of medicines to block the replication of the virus. the increased use of antiretroviral therapy (ART) has been accompanied by a concerning rise in HIV drug resistance. All antiretroviral drugs, including those from newer classes, are prone to becoming partially or fully ineffective due to drug-resistant viral strains. In a different example, antiviral drugs are important for the treatment of epidemic and pandemic influenza. As of right now, all influenza A viruses circulating in humans are resistant to one category of antiviral drugs – M2 inhibitors (amantadine and rimantadine).

Emerging Solutions

Last year, around 700,000 people died from antibiotic-resistant infections, but a study commissioned by the UK government, estimated that number could climb to 10 million annually—more deaths than from cancer.

The consequences of antibiotic resistance are staggering. Beyond the enormous strain on global healthcare systems, hospitals—especially intensive care units, transplant wards, and long-term care facilities—have become hotspots where resistant infections thrive. The most vulnerable patients, including the immunocompromised, newborns, and the elderly, face the highest risks. Treatment options are increasingly limited: new antibiotics bring only temporary relief before resistance inevitably emerges, sometimes forcing clinicians to rely on more toxic drugs—or leaving them with no effective options at all. It is clear that antibiotics alone cannot win this fight. To turn the tide, we must pursue innovative therapies that go beyond traditional drugs and target resistance from new angles.

Phage Therapy

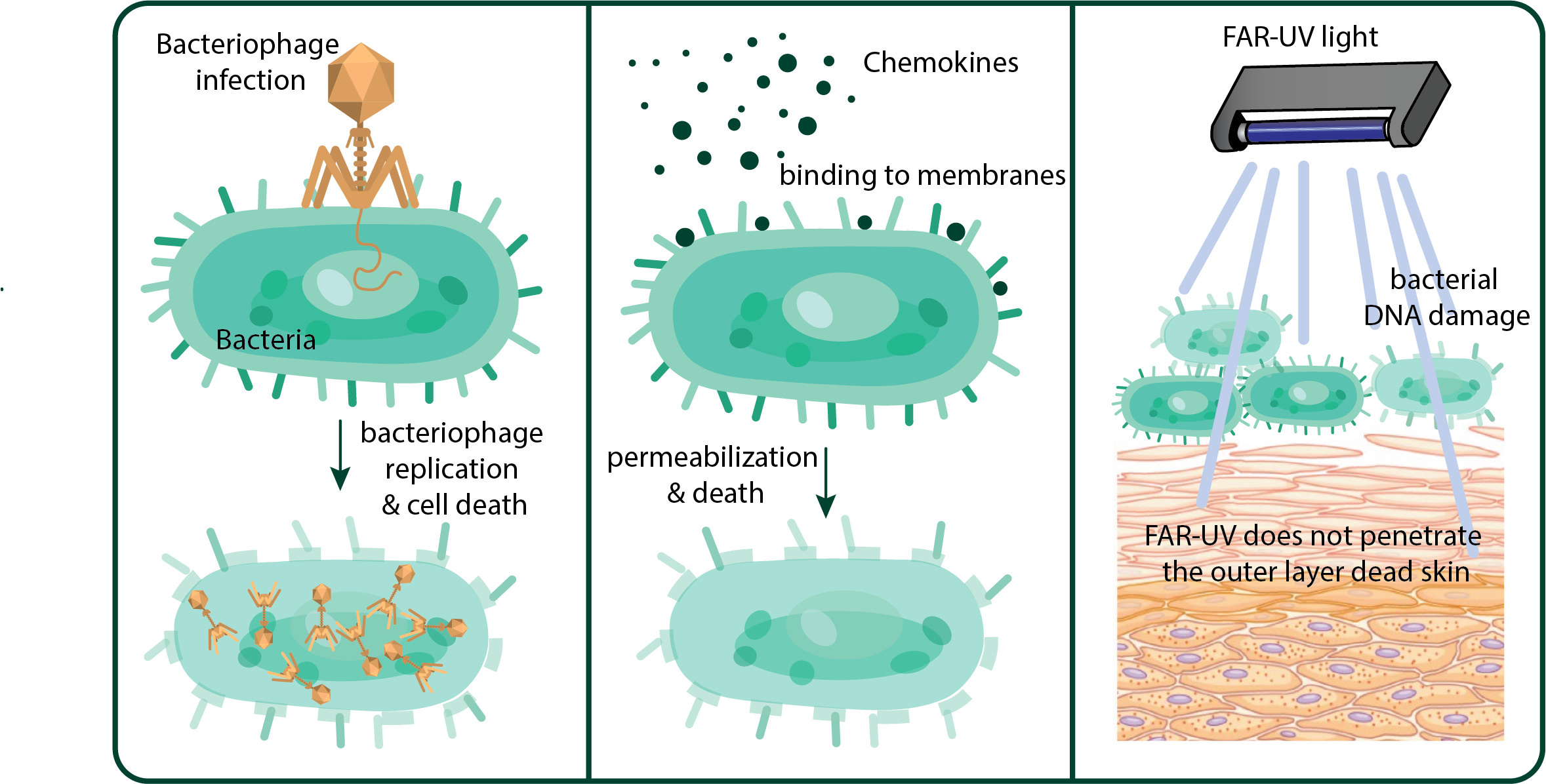

Viruses that specifically infect and kill bacteria are making a clinical comeback. Phage therapy harnesses bacteriophages as an alternative to antibiotics, offering a highly targeted way to fight resistant strains. Unlike broad-spectrum drugs, phages recognize distinct bacterial receptors, inject their genetic material, and hijack the host’s machinery to replicate. This rapid multiplication causes the bacterial cell to burst, releasing new viral particles that continue the cycle. Because phages amplify only at the site of infection, they spare beneficial microbiota and reduce collateral damage.

But how are phages selected for treatment? In most cases, clinicians start by isolating the bacterial strain from the patient—say, from a wound swab, blood culture, or respiratory sample. That isolate is then tested against large phage libraries, often maintained in academic labs, biotech companies, or national “phage banks.” The goal is to identify one or more phages that effectively infect and kill the patient’s specific bacterial strain. When a single phage isn’t enough, cocktails of multiple phages are often used to broaden coverage and reduce the chance of resistance.

Delivery methods vary depending on the infection site. Phages can be given orally, applied topically (for wounds or burns), inhaled through nebulizers (for lung infections), or injected intravenously for systemic infections. Once inside the body, they begin working almost immediately by replicating at the site of infection. Recovery times depend on the severity of the infection: in some compassionate-use cases, patients with life-threatening multidrug-resistant infections have shown improvement within days, though complete recovery can take weeks.

Is this still experimental? Yes and no. While phage therapy is not yet broadly approved in the U.S. or Europe, it is used routinely in countries like Georgia and Poland, where specialized phage institutes have decades of experience. In the West, phage therapy has mainly been provided under “compassionate use” or “expanded access” programs for patients with no other treatment options, and several Phase I/II clinical trials are now underway to formally test safety and efficacy. Encouragingly, early results show phages can be both safe and effective, especially against multidrug-resistant infections that fail conventional therapies.

A major advantage of phage therapy is adaptability. When bacteria develop resistance, new phages can often be found in environmental reservoirs such as sewage or engineered to restore activity, creating a dynamic treatment strategy. Early clinical cases and recent trials have demonstrated efficacy against multidrug-resistant pathogens, particularly in infections unresponsive to conventional drugs. Phages may also be combined with antibiotics to boost bacterial clearance and reduce the risk of resistance.

As with any emerging therapy, challenges remain. Their narrow host range requires tailored phage cocktails, regulatory pathways are still evolving, and immune responses may limit effectiveness in some patients. Even so, growing clinical successes and advances in synthetic biology are fueling momentum for phage therapy as a precision tool in the fight against superbugs.

Antimicrobial Peptides and Chemokines

Antimicrobial peptides such as chemokines are emerging as promising alternatives to traditional antibiotics in the fight against resistant bacteria. Unlike antibiotics, which usually target specific enzymes or pathways inside bacterial cells, chemokines act by binding to negatively charged phospholipids—particularly cardiolipin—in bacterial membranes, causing rapid permeabilization and cell death. This mechanism makes it far more difficult for bacteria to evolve resistance, since the random DNA changes that typically drive adaptation do not alter the membrane structures targeted by chemokines.

A recent study has shown that chemokines like CCL20 not only kill a wide range of pathogens but also retain their effectiveness across bacterial generations, underscoring their potential as a new class of broad-spectrum antimicrobials. However, chemokines also play key roles in the immune system by binding to receptors on immune cells and directing them to infection sites. These additional functions can limit their efficiency in a physiological environment. The current challenge is to identify the specific elements within chemokines responsible for their bactericidal activity, so that smaller, more focused versions can be engineered to preserve antimicrobial power while minimizing unwanted effects.

Far-UVC Light

Far-UV light, a newer branch of germicidal UV technology, is emerging as a practical solution for disinfecting indoor air — and in some cases, it’s already in use. Unlike conventional UVC (254 nm), which is effective but harmful to skin and eyes, far-UV at 222 nm inactivates bacteria and viruses without penetrating beyond the outer dead cell layers of skin or the tear film of the eye. This safety profile makes it possible to use far-UV directly in occupied spaces such as schools, restaurants, and even piano bars. Unlike air filtration or chemical disinfectants, far-UVC provides continuous, real-time protection by neutralizing viruses and bacteria as they float in the air. Studies show that it can effectively inactivate influenza, coronaviruses, and drug-resistant bacteria, all without contributing to antimicrobial resistance. While large-scale trials are still underway, the technology is no longer confined to the lab — it’s quietly becoming part of our everyday defense against infectious disease.

Scaling this technology will require careful regulation, safety standards, and cost-effective deployment, but the vision is compelling: passive, background protection against epidemics and everyday infections alike. In a world facing rising antibiotic resistance and recurring pandemics, far-UVC light offers a promising non-pharmaceutical intervention.

Three emerging solutions for antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Phage therapy: bacteriophages are introduced into the patient, where they specifically infect resistant bacteria, replicate, and kill them by bursting the cells. Chemokines: these molecules have bactericidal properties by binding to bacterial membranes, creating pores that disrupt permeability and ultimately kill the cell. Far-UVC light: more than a treatment, this is a safe sterilization tool that prevents the spread of resistant bacteria and viruses in public spaces. It kills microbes by damaging their DNA but is harmless to humans because it cannot penetrate beyond the outer dead layer of skin.

The Future Challenge

The rise of antibiotic-resistant bacteria is not some distant science fiction scenario—it’s happening right now. Without decisive action, we risk entering a post-antibiotic era where even minor injuries could carry serious consequences. The encouraging news is that science is actively developing innovative solutions, from engineered viruses to light-based sterilization, giving us a fighting chance. Still, success won’t come from technology alone. Policy and global cooperation will have to join the party. And while I’m fully confident in the science part, I sometimes wonder: if we can argue about the shape of the Earth in 2025, will we really manage to get our act together in time?

Would you like to stay updated on the latest breakthroughs in biomedical science? Subscribe to my blog and join me in exploring the next frontier of medicine!